New Rule Threatens Environment, Puts U.S. Waters at Risk

(AAAS 記事) 元記事公開日: 2020/8/14

「政策の科学」関連 海外情報 期間:8月13日~8月19日

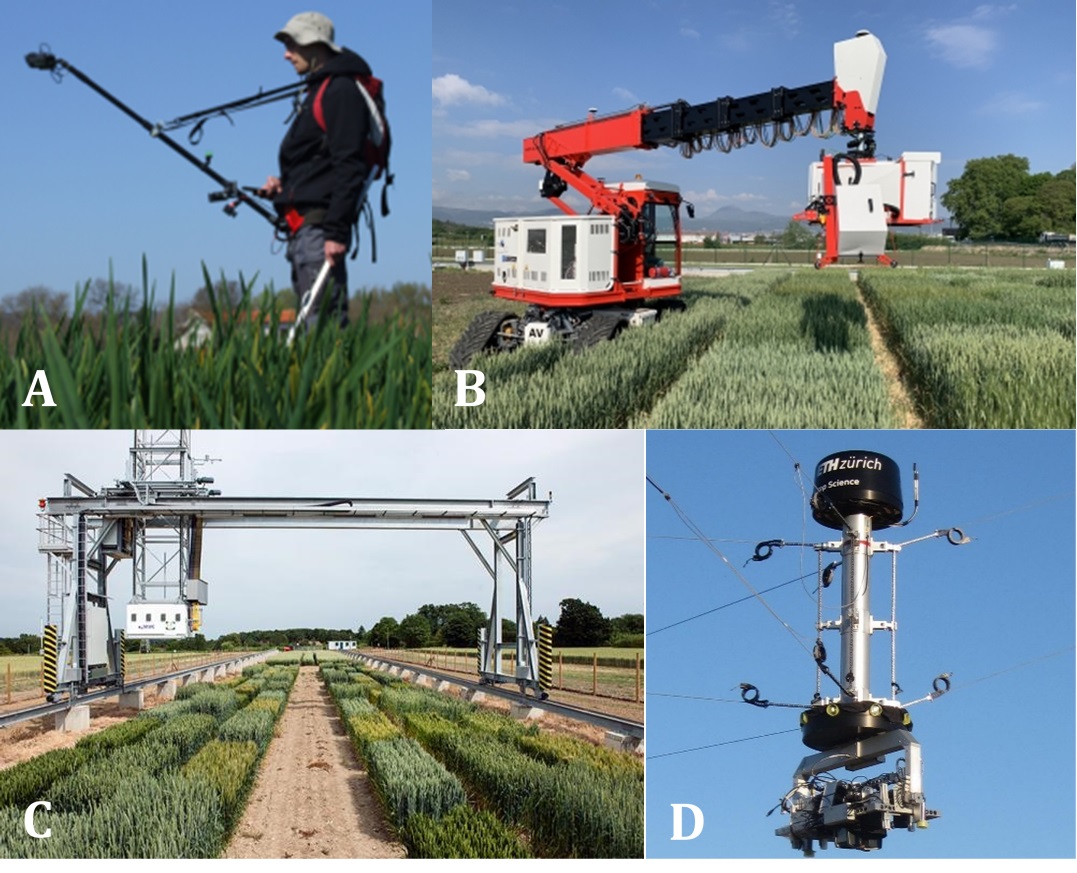

Science誌(8月13日号)によると、米国環境保護庁(EPA)と陸軍省によって公布され、6月22日施行された「可航水域保護規則」(NWPR)は、環境保護の大きな後退であり、米国の水系に広範囲にわたる長期的な害を及ぼす可能性があるとしている。規則では「米国の水域」と見なされる水域を再定義している。「連続的な地表のつながり」および「永続性」に焦点を当てており、水質浄化法(CWA)の保護・規制対象となる「米国の水域」に分類される範囲を狭めている。このルール変更により、数百万マイルの小川や広大な湿地に対する保護が事実上、削減または停止される。その多くは非常に脆弱な地域であるが、米国全土の流域の水質と健康を維持するために非常に重要なものである。

New Rule Threatens Environment, Puts U.S. Waters at Risk

14 August 2020 by: Walter Beckwith

Protected versus unprotected waters under the Navigable Waters Protection Rule. | Melissa Thomas Baum/Science

Protected versus unprotected waters under the Navigable Waters Protection Rule. | Melissa Thomas Baum/Science

The Trump administration’s recently finalized Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR) represents a major rollback in environmental protections and has the potential to cause widespread and long-lasting harm to U.S. waters, according to a Policy Forum published in the August 13 issue of Science.

The rule, which was published by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of the Army, redefines what waters are considered “waters of the U.S.” With its focus on “continuous surface connections” and “permanence,” the NWPR narrows the scope of what are classified as U.S. waters, and, thus, subject to protection and regulation within the Clean Water Act, the primary federal law governing water pollution in the United States.

However,the NWPR’s redefinition significantly deviates from previous administrations’ interpretation of the Clean Water Act, and is largely inconsistent with the best available science concerning water and watersheds — particularly on how connections between waters are critical for their function.

“For example, over half of our nation’s small or temporary streams — many of which have now lost protection — feed the public water systems that support one-third of Americans in the continental U.S.,” said Amanda Rodewald, a Policy Forum co-author from Cornell University. “With roughly half of U.S. streams and rivers already in poor condition, now is not the time to weaken protections.”

The rule’s changes, which went into effect on June 22, effectively reduce or remove protections for millions of miles of streams and acres of wetlands, many of which are highly vulnerable areas, yet crucial to sustaining the quality and health of watersheds across the nation.

“These streams and wetlands are vital ecosystems that both directly and indirectly provide a range of ecosystem services, including providing drinking water, reducing floods and generating billions of dollars to the U.S. economy,” said Mažeika Sullivan, the paper’s lead author and a researcher at The Ohio State University.

“The waters that that were removed from federal protection by the Navigable Waters Protection Rule are critical for ensuring healthy watersheds, water quality, and human well-being,” said Sullivan. “In implementing this rule, the federal government has set science aside — against the advice of the U.S. EPA’s own Science Advisory Board — and weakened water protections across the country.”

The 1972 Clean Water Act is one of the United States’ first and most influential modern environmental mandates. The act’s objective is to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the nation’s waters.” The exact definition of these waters has varied over time, and, as a result, protection of some areas, particularly non-traditional, non-navigable waterbodies like wetlands, small tributary streams or ephemeral ponds, for example, have remained contentious and subject for legal debate.

Many of these waters form the backbone of watersheds and contribute to the integrity of larger traditional navigable waterways. Largely based on the scientific understanding of how freshwater systems and their ecosystem functions are maintained, this connectivity was recognized in the Obama administration’s 2015 Clean Water Rule, which more clearly and consistently defined the scope of federal waters protection to include these less permanent and navigable waterbodies.

However, citing concerns and criticisms of the rule’s effect on economic growth, the Trump administration rolled back the previous protections of the 2015 rule and published the NWRP.

“Non-floodplain wetlands and ephemeral streams — both of which have categorically lost federal protection under the NWPR — are considered among the most vulnerable waters and have been disproportionately impaired or destroyed by a suite of human activities when compared to other waterbodies,” said Sullivan.

“Keep in mind that this isn’t a question of a small set of waters — we’re talking about millions of miles of streams and millions of acres of wetlands. In many areas of the country — especially in the arid West — ephemeral streams comprise the majority of stream miles,” he added.

Many of these excluded waters offer important ecosystem services that larger, traditional water systems do not, such as supplying drinking water, recharging groundwater aquifers, preventing floods and improving water quality by trapping sediment and pollutants.

In contrast to the Clean Water Rule — which was built on more than 1200 peer-reviewed scientific publications and extensive professional input — the NWPR deviates from scientific understanding and relies solely on direct hydrologic surface connectivity to determine wetland jurisdiction.

According to Sullivan, the NWPR distorts, disregards or selectively excludes important environmental and ecological underpinnings of waterbody connectivity, despite the strong scientific evidence that demonstrates its critical nature. The NWPR’s sole focus on surface-water flow directly contradicts the Clean Water Act’s precise language outlining the protection of the “chemical, physical and biological integrity” of U.S. waters, said Sullivan.

While the agencies involved maintain that the new rule’s changes seek to define U.S. waters in a clearer and more understandable way, the NWPR ignores well established scientific understanding and even explicitly states that “science cannot dictate where to draw the line between federal and state water,” according to Sullivan and the researchers.

“The existing research on waterbody connectivity is excellent, and offers strong rationales against removing ephemeral streams, non-floodplain wetlands, and other waters from protection,” said Sullivan.

“However, in light of the fact that the NWPR went into effect on June 22 of this year, as scientists, we are now tasked with demonstrating, and in fact quantifying, the harm the NWPR will cause to watersheds and water quality.”

[Credit for associated image: Nicholas A. Tonelli/ Flickr]