2023-03-07 オランダ・デルフト工科大学(TUDelft)

船舶産業はセンサーや人工知能を用いた自動運航に取り組み、安全性向上や環境保護にも繋がる。しかし、5万隻以上の商船が150か国の国旗の下で世界中で運航しており、海上交通制御センターなどの技術的・経済的な環境整備が急務である。

このような状況下で、自動船が期待される課題や研究課題について6つのキーポイントを解説する。

(i)自律性の異なるレベルにおける課題の理解。

(ii)人間の役割を定義する。

(iii)安全とセキュリティを確保する。

(iv)港湾の再考。

(v)法的及び規制の枠組みに自律性を組み込むこと。

(vi)自律船に関する事例の提示する。

<関連情報>

- https://www.tudelft.nl/en/2023/3me/news/rudy-negenborns-vision-on-autonomous-ships-in-nature

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00557-5

自律型船舶の実現が目前に迫っている:私たちが知るべきことはこれだ

しかし、海事産業が実用的、法的、経済的な影響を最初に解決することができればの話です。

Autonomous ships are on the horizon: here’s what we need to know

Ships and ports are ripe for operation without humans — but only if the maritime industry can work through the practical, legal and economic implications first.

Rudy R. Negenborn,Floris Goerlandt,Tor A. Johansen,Peter Slaets,Osiris A. Valdez Banda,Thierry Vanelslander & Nikolaos P. Ventikos

Nature Published: 27 February 2023

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00557-5

By 2024, the Norwegian container ship Yara Birkeland is expected to carry fertilizer autonomously from plant to port with zero emissions. Credit: Torstein Bøe/NTB/AFP via Getty

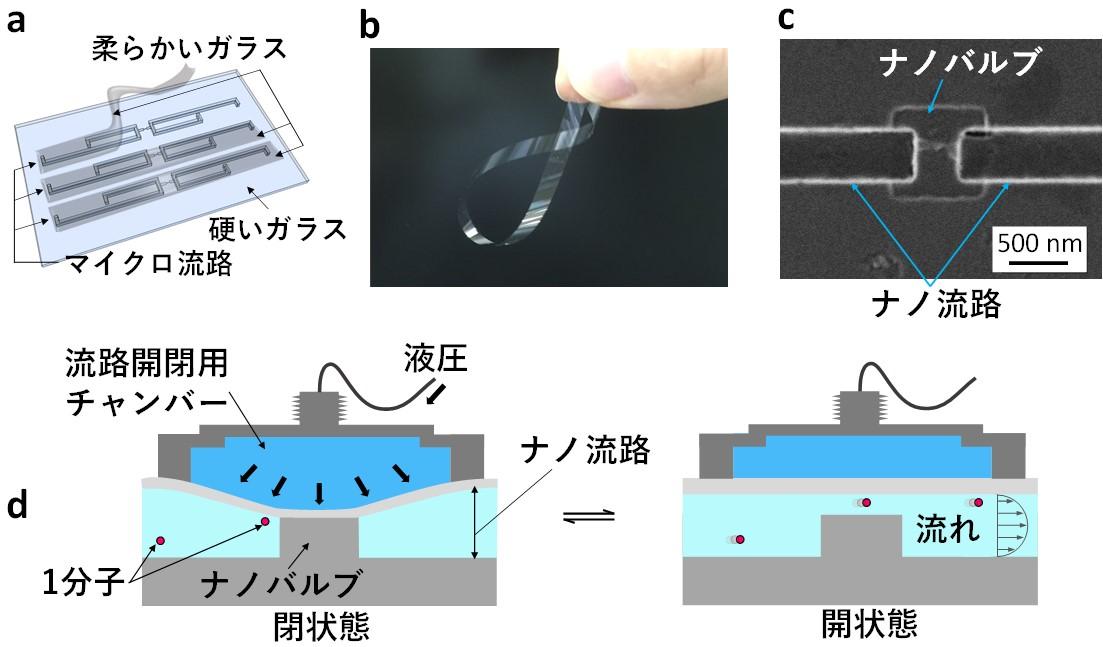

In January last year, a Japanese car ferry, the Soleil, became the first large vessel to navigate without human intervention. The 220-metre-long ship automatically berthed and unberthed, turned, reversed and steered itself for 240 kilometres across the Iyonada Sea from Shinmoji in northern Kyushu — manoeuvres that even skilled human operators find challenging.

It is early days, but ships are increasingly deploying sensors and artificial-intelligence (AI) systems to navigate, steer and avoid collisions. As with cars, such advances should improve safety, increase efficiency and — along with cleaner fuels and engines — reduce environmental impacts.

This is crucial: 80% of global trade (around 11 billion tonnes) is transported by sea each year1. In 2018, shipping generated around 3% (about 1,000 million tonnes) of global carbon dioxide emissions2. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has committed to halving the industry’s greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050.

Seafaring is risky and workers are in short supply. Inefficiencies and congestion at ports add delays and costs, as do accidents, such as the grounding of the container ship Ever Given in the Suez canal for six days in March 2021. Streamlining passage through locks, reducing energy consumption and negotiating manoeuvres to avoid collisions would enable safer and more optimal use of waterways.

Some small, fully autonomous boats, typically less than 10 metres long, are already in operation for specialist tasks such as monitoring water quality and infrastructure in the open sea, or as test beds for the technology. But the next couple of years will see a sea change, with the first larger ‘maritime autonomous surface ships’ planned to start commercial operation.

A cleaner future for flight — aviation needs a radical redesign

Pilot projects include the Norwegian container ship Yara Birkeland, an 80-metre-long vessel that, by 2024, is expected to convey fertilizer autonomously and with zero emissions from a manufacturing plant to an export port. In China, a 120-metre-long electric container ship called Zhi Fei has been demonstrated shuttling under remote (and sometimes autonomous) control between two ports in Shandong province.

In a decade, automated vessels might interact with one another. For instance, the Vessel Train, a pilot project funded by the European Union and coordinated by the Netherlands Maritime Technology Foundation in Rotterdam, uses a crewed lead vessel to head a convoy of smaller, automated ones that can access small waterways around ports efficiently. Ultimately, fleets of self-steering ships or boats might be managed from maritime traffic-control centres located on shore.

But if autonomous vessels are to fulfil their promise, much remains to be done — and soon. More than 50,000 merchant ships trade internationally, under the flags of some 150 nations. A large, high-tech vessel can cost US$200 million to build, and can operate for decades. Ships are complex technically. They need to work in busy shipping lanes, ports and rough open seas.

Combining maritime systems is daunting — from radar, satellites and GPS, cameras and sensors, to image recognition, data analytics and machine-learning algorithms. And autonomous ships need to be plugged into a broader ecosystem of maritime technologies, including interactions between ships and with cargo handlers, equipment, pilots, traffic services and ports.

Here, we highlight research gaps in six key areas.