2025-10-17 マサチューセッツ大学アマースト校

<関連情報>

- https://www.umass.edu/news/article/cybersecurity-institutes-spin-research-group-earns-recognition-work-internet-freedom

- https://www.ndss-symposium.org/wp-content/uploads/2025-237-paper.pdf

- https://gfw.report/publications/usenixsecurity25/data/paper/quic-sni.pdf

- https://people.cs.umass.edu/~amir/papers/UsenixSecurity23_Encrypted_Censorship.pdf

ウォールブリード:中国のグレートファイアウォールにおけるメモリ漏洩脆弱性 Wallbleed: A Memory Disclosure Vulnerability in the Great Firewall of China

Shencha Fan,Jackson Sippe,Sakamoto San,Jade Sheffey,David Fifield,Amir Houmansadr,Elson Wedwards,Eric Wustrow

Abstract

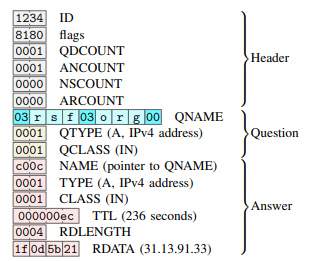

We present Wallbleed, a buffer over-read vulnerability that existed in the DNS injection subsystem of the Great Firewall of China. Wallbleed caused certain nation-wide censorship middleboxes to reveal up to 125 bytes of their memory when censoring a crafted DNS query. It afforded a rare insight into one of the Great Firewall’s well-known network attacks, namely DNS injection, in terms of its internal architecture and the censor’s operational behaviors.

To understand the causes and implications of Wallbleed, we conducted longitudinal and Internet-wide measurements for over two years from October 2021. We (1) reverse-engineered the injector’s parsing logic, (2) evaluated what information was leaked and how Internet users inside and outside of China were affected, and (3) monitored the censor’s patching behaviors over time. We identified possible internal traffic of the censorship system, analyzed its memory management and load-balancing mechanisms, and observed process-level changes in an injector node. We employed a new side channel to distinguish the injector’s multiple processes to assist our analysis. Our monitoring revealed that the censor coordinated an incorrect patch for Wallbleed in November 2023 and fully patched it in March 2024.

Wallbleed exemplifies that the harm censorship middleboxes impose on Internet users is even beyond their obvious infringement of freedom of expression. When implemented poorly, it also imposes severe privacy and confidentiality risks to Internet users.

グレート・ファイアウォールにおけるSNIベースのQUIC検閲の暴露と回避 Exposing and Circumventing SNI-based QUIC Censorship of the Great Firewall of China

Ali Zohaib,Qiang Zao,Jackson Sippe,Abdulrahman Alaraj,Amir Houmansadr,Zakir Durumeric,Eric Wustrow

Abstract

Despite QUIC handshake packets being encrypted, the Great Firewall of China (GFW) has begun blocking QUIC connections to specific domains since April 7, 2024. In this work, we measure and characterize the GFW’s censorship of QUIC to understand how and what it blocks. Our measurements reveal that the GFW decrypts QUIC Initial packets at scale, applies heuristic filtering rules, and uses a blocklist distinct from its other censorship mechanisms. We expose a critical flaw in this new system: the computational overhead of decryption reduces its effectiveness under moderate traffic loads. We also demonstrate that this censorship mechanism can be weaponized to block UDP traffic between arbitrary hosts in China and the rest of the world. We collaborate with various open-source communities to integrate circumvention strategies into a leading web browser, the quic-go library, and all major QUIC-based circumvention tools.

中国のグレートファイアウォールはどのようにして完全に暗号化されたトラフィックを検知し、ブロックするのか How the Great Firewall of China Detects and Blocks Fully Encrypted Traffic

Mingshi Wu,Jackson Sippe,Danesh Sivakumar,Jack Burg,Peter Anderson,Xiaokang Wang,Kevin Bock,Amir Houmansadr,Dave Levin,Eric Wustrow

Abstract

One of the cornerstones in censorship circumvention is fully encrypted protocols, which encrypt every byte of the payload in an attempt to “look like nothing”. In early November 2021, the Great Firewall of China (GFW) deployed a new censorship technique that passively detects—and subsequently blocks— fully encrypted traffic in real time. The GFW’s new censorship capability affects a large set of popular censorship circumvention protocols, including but not limited to Shadowsocks, VMess, and Obfs4. Although China had long actively probed such protocols, this was the first report of purely passive detection, leading the anti-censorship community to ask how detection was possible.

In this paper, we measure and characterize the GFW’s new system for censoring fully encrypted traffic. We find that, instead of directly defining what fully encrypted traffic is, the censor applies crude but efficient heuristics to exempt traffic that is unlikely to be fully encrypted traffic; it then blocks the remaining non-exempted traffic. These heuristics are based on the fingerprints of common protocols, the fraction of set bits, and the number, fraction, and position of printable ASCII characters. Our Internet scans reveal what traffic and which IP addresses the GFW inspects. We simulate the inferred GFW’s detection algorithm on live traffic at a university network tap to evaluate its comprehensiveness and false positives. We show evidence that the rules we inferred have good coverage of what the GFW actually uses. We estimate that, if applied broadly, it could potentially block about 0.6% of normal Internet traffic as collateral damage.

Our understanding of the GFW’s new censorship mechanism helps us derive several practical circumvention strategies. We responsibly disclosed our findings and suggestions to the developers of different anti-censorship tools, helping millions of users successfully evade this new form of blocking.